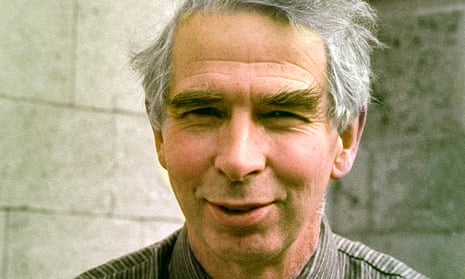

Alastair Hanton, who has died aged 94, was a banker and pioneer of ethical investment and fair trade, as well as a green transport campaigner. Through his innovations, he transformed the day-to-day experience of banking for ordinary British people.

He introduced the system of direct debit to the UK, pushing a cartel of traditional banks to adopt more flexible payment practices in the 1960s. At the National Girobank, the people’s bank set up by the Labour government at the end of that decade, he was the driving force behind free bank accounts – giving millions of people the service for the first time. Turning the Link system of cashpoints into one in which any customer of any bank could withdraw money from any machine without charge was another of his ideas.

His career as an innovator in industry and banking was followed by three equally productive decades as a founding father of the UK fair trade movement and a campaigner for ethical investment and greener, safer transport.

His idea for direct debits was conceived when he was working in the economic research department of Unilever, which needed to collect irregular payments from thousands of small-business sellers of ice cream. He persisted in lobbying the big banks until they accepted the change in 1964.

But it was an advertisement for a new national bank in 1968 that led to him finding his calling. Harold Wilson’s government – frustrated at the failure of established banks to provide services for the masses, most of whom could not afford their charges and lived in areas where banks did not deign to offer branches – was intent on founding a people’s bank to shake up the sector. It decided that the vast network of post offices across the country could provide a ready-made infrastructure for what would become the National Girobank.

Hanton rushed to apply and was made director of operations. Working under a series of politically appointed banking grandees, he set about transforming the banking sector.

Well before slogans about “levelling up” became fashionable, Hanton successfully advocated locating the centre of operations in Bootle, Merseyside, to bring employment to a deeply deprived area. Under his management the National Girobank pioneered computerised payment systems, optical character recognition that made instant credits and quick utility bill payments possible, and created the first interest-paying current accounts. Hanton saw his mission as preventing the poor, who often kept their cash under their beds, being robbed twice over, by burglars and by inflation.

The early 70s were a touch-and-go period for the new bank, however. Edward Heath’s Conservative government, encouraged by a hostile Daily Telegraph and Daily Mail, thought about abolishing the fledgling institution, which had lost money in the early years. But by then Hanton had managed to make it turn a tiny profit and it was allowed to continue. Thereafter it grew rapidly and its innovative practices galvanised British banking.

Hanton, who had by then been made CEO, was appointed OBE on retirement from the bank in 1986.

Born in north London, Hanton was the eldest son of Maud (nee Evans), a secretary, and Peter Kydd Hanton, a public works architect. He attended Mill Hill school before reading economics and mathematics at Pembroke College, Cambridge.

On graduation in 1948 he joined what was the British government’s overseas aid financing body, the Colonial Development Corporation (now the Commonwealth Development Corporation, or CDC) and was posted to Malawi, where a passion for social and trade justice was ignited.

Back in the UK, he married Margaret Lumsden, a fellow Cambridge graduate who was working in market research, in 1956. Spells followed at the Bank of England’s Industrial and Commercial Finance Corporation, promoting funding for small businesses, then at Unilever (1958-64) and the mining company Rio Tinto Zinc before the National Girobank. It was during this period that he and Margaret invited a Nigerian couple and their four children, who needed a home, to spend three years sharing the large house in Dulwich, south London, in which they had settled.

While still at the bank Hanton began his efforts to make ethics a priority in investment. In 1985 he joined forces with a nascent initiative from church and charity groups, Ethical Investment Research Information Services (Eiris), to gather information on whether funds were invested in arms, tobacco, or apartheid-tainted activities. He joined the board of Eiris when it was incorporated in 1986, and served as an active chair and then trustee into his 90s, helping launch the FTSE4Good and other programmes. Eiris is now widely used by trade unions, churches, NGOs and fund managers to check the probity of their investments.

A practising Methodist, on retirement Alastair became a trustee, and later vice-chair, of Christian Aid, and in that role was a driving force behind campaigns for debt relief for poor countries and the growth of the fair trade movement. The Fair Trade Foundation was created in 1992 by a group of leading UK aid charities, including Christian Aid, Oxfam and Cafod, with the aim of making sure a fairer share of profits for goods went back to producing countries. Hanton became its chair and brought together the disparate organisations skilfully, encouraging them to expand fair trade into the mainstream of retail.

Those who worked with him describe his deep humility and generosity. Hanton was effective because he saw leadership not as a power role but as one of service and enabling others.

His other lifelong passion – for cycling, walking and greener transport – began when his school was evacuated to Cumbria during the second world war and he and his brother would cycle back home to London for holidays. He was a frequent donor and tireless activist, often acting as trustee or chair, for dozens of campaign groups. Living Streets, the London Cycling Campaign, Airport Watch, Campaign for Better Transport and the Foundation for Integrated Transport were just a few among them.

Hanton had a clear-sighted grasp of the importance of influencing policy at the national level — he took his campaign to abolish tax breaks for company cars and ban bull bars, which he showed caused disproportionate fatalities on UK roads, to a parliamentary select committee in 2001, for example, and was rewarded with success. But he gave as much time and effort to small practical actions to make things better. He believed strongly that individuals could make a real difference if they worked collectively, and were patient and persistent enough.

Margaret survives him, as do their three children, Fiona, Angus and Bruce, 13 grandchildren and seven great-granddaughters.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion