Kwak Nga was still reeling from her husband’s suicide when his microfinance creditors showed up at her home to remind her that they still expected the approximate $170 (£140) monthly interest payments the couple had struggled to make.

Nhu Laen killed himself at his farm in November 2022. In the months before his death, LOLC Cambodia, one of Cambodia’s leading microfinance institutions, granted Laen a loan that tripled his debt with the company to more than $18,000, even though, according to Nga, the couple had already been encouraged by LOLC to borrow from other lenders to help repay previous outstanding microloans.

“That [new microloan] was too big an amount – this family is very poor,” says Chav Kham, the chief of Prak II village in north-east Cambodia’s Ratanakiri province, where the couple lived.

Cambodia represents one of the world’s largest microlending sectors by loans per capita, with loans totalling $16bn (£13bn), but some of the biggest microloan companies in the country are under the scrutiny of the World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) for harms allegedly caused by lending, including “loss of land, livelihood impacts, impacts on Indigenous peoples, and threats and reprisals”.

Being heavily in debt led to Laen’s suicide, his wife says. In three other cases in north-east Cambodia, debt-related stress may have played a role in a microloan borrower’s suicide or attempted suicide, according to family members and neighbours.

Laen and Nga used most of the money they borrowed from LOLC Cambodia in April 2022 to repay existing debt stemming from earlier LOLC microloans. With the rest of the loan, the couple bought a small plot of land to grow soya beans, cassava and cashews, dreaming of a farm that would one day provide them with a better livelihood.

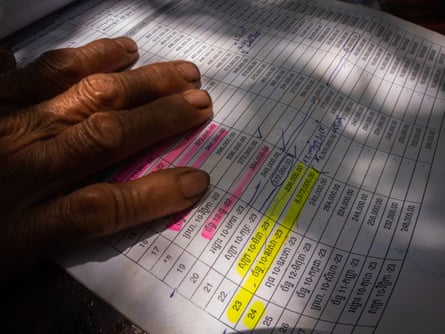

But between May 2022 and May 2023, they were expected to repay LOLC Cambodia more than $4,300, their loan documents state. This amount was well above their annual income of an estimated $2,200.

Laen made just $6 a day working intermittently on other people’s fields while simultaneously trying to prepare his own farmland, leaving him sick with exhaustion, Nga recalls.

Nga claims that LOLC’s credit officers encouraged her and Laen to use neighbourhood lenders charging as much as 20% monthly interest to keep up with LOLC Cambodia’s repayment schedule. Nga’s elderly parents, who lived with the couple, also took out a $1,000 loan from another microfinance institution, AMK, to help them repay their accumulating debts.

Nga and Laen had hoped to make about $725 from their year-end harvest in 2022, but months of bad weather meant they only made $300 in the entire year. Yet they owed more than $650 a month in interest alone by November to various microfinance institutions and loan sharks.

“My husband died because of debt,” says Nga.

She says that after Laen’s suicide she repeatedly sought debt relief from LOLC Cambodia, which held the land titles for her farm and home as collateral. It was only when the Cambodian human rights NGO Licadho wrote directly to the chair of LOLC Cambodia – four months after Laen’s death – that the company’s credit officers stopped demanding repayment.

Since the 1990s, Cambodia’s microfinance industry has received hundreds of millions of dollars directly and indirectly from the IFC and US and European governments to provide microloans intended to lift Cambodians out of poverty by increasing their access to credit. Industry proponents argue that microloans have reduced the country’s poverty rate and fuelled the growth of small businesses.

While many microlenders, such as LOLC Cambodia, were initially part of nonprofits, they have transformed into private sector, profit-driven companies. LOLC Cambodia, originally run by a Catholic charity, is now owned by a Sri Lankan holding group, and reported a $58.7m profit last year.

Allegations of debt-driven distress are now being reviewed by the IFC’s compliance advisor ombudsman. In August, the ombudsman launched an investigation of the IFC’s investment into six of Cambodia’s leading microfinance firms, stating that there were “preliminary indications of harm” to borrowers, including coerced land sales, forced migration and children dropping out of school.

The IFC ombudsman’s investigation was prompted by a complaint filed last year by Licadho and another human rights NGO, Equitable Cambodia, on behalf of borrowers who alleged they had been victims of “predatory”, “deceptive” and “irresponsible” loans and collection tactics by the six microlenders, all of which receive direct or indirect IFC funding and comprise about 75% of Cambodia’s microfinance market.

Four of the institutions under IFC investigation – Amret Microfinance Institution, LOLC Cambodia, Hattha Bank and Sathapana Bank – had active loans with at least one borrower who killed themselves and one who attempted suicide, according to their families and the borrowers’ loan documents, seen by the Guardian. One borrower also had an active loan with Phillip Bank and Nga says she and her husband were responsible for her parents’ loan from AMK Microfinance Institution.

The borrowers were all members of Indigenous ethnic minority communities in Ratanakiri, one of Cambodia’s poorest regions, where people often do not fluently speak or read Khmer, the country’s dominant language. The IFC’s investigation is also assessing whether microlenders may have violated the IFC’s strict policies protecting Indigenous peoples.

As well as Laen, the others who died include a husband who had an affair and was required to pay financial compensation to divorce, in accordance with local custom, which he could not afford along with his debt, his wife and parent-in-laws say. There was also a struggling cashew farmer burdened with repayments for a number of microloans.

“A few months before his suicide, he always complained: when he got paid for his work he paid back the bank and private lenders but it was never enough, still more was required,” says the cashew farmer’s wife, Hyan Ayean. “He always brought up the debt and his negative thoughts. We were afraid of not having any money for the bank.”

In another case, a 17-year-old girl from the same area attempted suicide in March. Her father claims that Amret employees, seeking to collect on a microloan debt of more than $50,000 that he owed, warned that the family would be placed on a “blacklist”, cutting off the girl’s future educational opportunities, and put pressure on the family to sell assets, including the motorbike their daughter used to travel to school.

“When my father called me to ask to sell the motorbike, I felt so stressed and I didn’t know who I could talk with,” says the girl, who asked not to be named, and who lived with relatives in a different province to access better education.

Five microlending institutions denied in statements that the suicides and attempted suicide had any connection to microloans. They claimed that internal company audits found the deaths and suicide attempt were caused by family and personal disputes or other factors.

Sathapana did not respond to requests for comment.

LOLC Cambodia’s chief executive, Sok Voeun, who is also the chair of the industry group Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA), which reviewed each of the six firms’ internal audits, said that in all cases there had been “no misconduct”. On 9 August, the CMA issued a statement calling for an independent investigation into the allegations. The National Bank of Cambodia, the industry’s regulator, did not respond to requests for comment.

But the allegations of microlenders’ actions contributing to the suicides and suicide attempt indicate “clear violation of the responsible practices” of the industry’s widely used Client Protection Standards, according to a joint statement by the organisations Cerise+SPTF, which set the standards.

These standards prohibit issuing loans that will consume more than 70% of a borrower’s disposable income, including accounting for debts to other informal lenders. They also bar credit officers from using threats against borrowers.

“We do not find responses of ‘no misconduct’ or ‘no causal connection’ to be sufficient,” the Cerise+SPTF statement said.

Cerise+SPTF requested that the microlenders Sathapana Bank, Amret, AMK and LOLC Cambodia have their client protection certifications placed under review as a result.

“There have been huge concerns around rapid growth and overheating in the Cambodian market,” says Frances Sinha, the director of M-CRIL, the financial ratings firm that certified AMK, Amret and Sathapana. “The warning signs have been there for some time.”

Cambodian borrowers’ average microloan sizes of about $9,000 are more than twice the median income of the country’s rural families, while the value of active microloans held by borrowers has doubled from $8bn in 2019 to $16bn, according to a recent study by Licadho and Equitable Cambodia.

The Cambodian industry’s soaring growth has been driven by direct and indirect government funding from the development banks and agencies of the US, Sweden, France, Norway, Finland, Austria, Belgium, the UK, the Netherlands and Germany.

One of the largest IFC and government-supported microfinance investment funds, the Microfinance Enhancement Facility, a major funder of LOLC Cambodia and Amret, has recently put new investment in Cambodia “on hold”, according to its co-manager Incofin Investment Management.

LOLC Cambodia’s CEO said that his company’s analysis of Laen and Nga’s cashflow indicated that they were capable of repaying their microloans when they were issued and that Laen’s suicide was triggered by the bad weather affecting his harvest.

LOLC Cambodia’s board of directors said: “There is no evidence … to any oppressive or unethical conduct on the part of LOLC Cambodia and/or its staff” and that “close relations of the deceased were unaware of any reasons for such suicide”.

LOLC Cambodia has since stopped requesting that Nga repay her microloan, but the neighbourhood lenders she borrowed from insist on repayment.

“I have no ability to repay,” says Nga. “I am afraid I will kill myself, like my husband.”

Additional reporting by Mech Choulay, Seoung Nimol, Eung Sea, Bang Sunny, Mong Vichet and Sim Tiv