The Treasury select committee doesn’t want to launch an inquiry into Greensill Capital – at least not yet. That decision is regrettable but the need for an investigation remains pressing. This saga isn’t merely about decisions taken in the fog of a pandemic. It is also about the terms on which politicians and officialdom should engage with business.

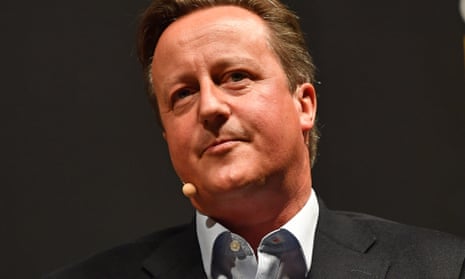

First, and most obviously, what was David Cameron up to in his role as adviser to Greensill? No doubt the former prime minister was cleared for the post under standard procedures for vetting ex-ministers’ appointments. So one could be generous and say Cameron was merely naive in taking a position with a finance outfit that failed and blew up his share options.

Yet Cameron’s lobbying efforts appear extraordinary. The FT reported last week that he had approached the Treasury and Downing Street via private email and telephone to try to increase Greensill Capital’s access to state-backed emergency Covid loan schemes. And the Sunday Times described a series of texts to Rishi Sunak, the chancellor.

Private channels of communication? Text messages? Undisclosed pressure on Treasury officials to revisit decisions to exclude Greensill from the Bank of England-backed Covid corporate financing facility (CCFF)? This is territory where only full account of what was said, and when, can tell us if current rules on lobbying are up to scratch. On the basis of what we know so far, the formal transparency demands look to be a joke.

Second, are the Treasury’s hands wholly clean? Tom Scholar and Charles Roxburgh, the two most senior Treasury officials, seem to have skilfully deflected Greensill’s appeals for access to the CCFF scheme in May 2020. But what was the process whereby the finance firm was approved as a lender under the separate coronavirus large business interruption loan scheme (CLBILS), the following month?

The CLBILS scheme is administered by the British Business Bank. Was it aware of the Treasury officials’ apparent doubts about Greensill? Was there communication between the two bodies? If so, what was said?

Third, under the CLBILS scheme, via which the government provided a 80% guarantee, Greensill appears to have massively breached its lending limits to one borrower – GFG Alliance and companies associated with the steel firm’s owner, Sanjeev Gupta. If the sum is as much as £400m, how could it go unnoticed until it was too late? The number of borrowers under the scheme was relatively small, remember.

Fourth, was the Financial Conduct Authority asleep? Trade finance is an unregulated activity, but the UK financial watchdog still had to supervise Greensill for compliance with anti-money laundering rules. What compliance checks were made? And, since even a brief inspection should have revealed Greensill’s over-reliance on a few clients, including Gupta’s companies, did the FCA warn the Treasury of possible dangers? Was the FCA curious about the many Greensill and Gupta-related written questions that Lord Myners, a former City minister, has been tabling in the Lords for the past two years?

The next chapter in this story may involve the UK public purse taking a financial whack if GFG unravels, which is the point at which the Treasury could face hard choices about how, or if, to rescue the underlying steel operations. Given the potential political stakes, let’s hear directly from the main players about how the mess was allowed to spread.

Mind-boggling valuation

Deliveroo would not have put a price tag of £7.6bn to £8.8bn on its flotation unless its investment bank advisers were confident of landing somewhere within the range. The big City fund managers have already indicated their interest, remember.

The valuation still looks mind-boggling, however. Yes, DoorDash in the US and Just Eat Takeaway in the UK have similarly lofty valuations. And, yes, the business is being priced on the assumption that the food delivery revolution is permanent and won’t be seriously slowed by the reopening of restaurants.

Even so, does anybody have even a vague idea of where Deliveroo’s net profit margins (as opposed to the irrelevant gross margins that the company keeps quoting) will land when profits eventually appear?

If the competition authorities are on the ball, putting food on the back of a bike should be a low-margin game, rather like selling food in supermarkets. At the top of the range, Deliveroo will be worth half a Tesco. Good luck to the buyers.