By all accounts, Otto Bremer was everything a community banker aspires to be: a successful, civic-minded guy who pumped the profits from his banks back into the small Midwestern towns where they operated.

He believed so strongly in the notion that in 1944 he formed a foundation — funded by regular dividends from his St. Paul, Minn., banking company's earnings — to invest in charitable projects throughout the area.

When he died wifeless and childless in 1951, Bremer left ownership of the company to the foundation. Ever since then, the organization — since renamed the Otto Bremer Trust — has been using the company's earnings to support charitable endeavors, as Bremer envisioned.

Today, the $13 billion-asset Bremer Financial finds itself locked in a

The trust's three trustees, who also sit on the Bremer Financial board, want to sell the company and, to aid their cause, have attempted to sell some of the trust's shares to a group of hedge funds.

Bremer Financial's seven non-trustee board members think the company is doing just fine as an independent entity and oppose the idea. They have filed suit to block the hedge funds' share purchase.

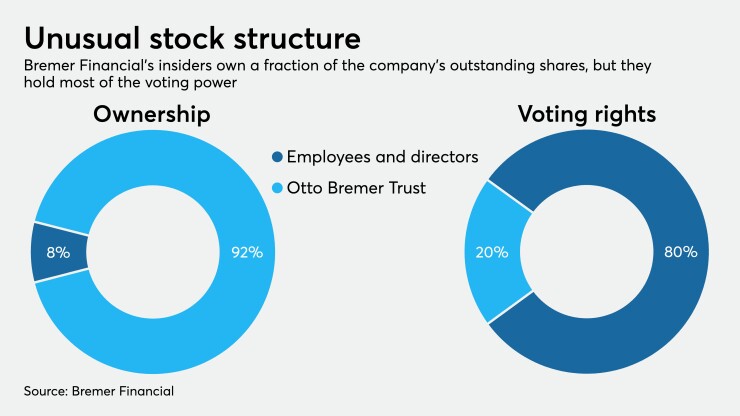

Who has the power to decide the institution's future could ultimately be determined by a judge. The trust owns 92% of Bremer Financial's "economic" shares, but has only 20% of the voting power. Employees own the remaining 80% of voting shares and 8% of economic shares.

In a November lawsuit, the seven non-trustee directors accuse the trustees of perpetrating a "disloyal scheme" to wrest control of the company from the board and enrich themselves.

Two of the trustees, Brian Lipschultz and Daniel Reardon, also receive investment-management fees, which are equal to about 30 basis points of the assets that are not affiliated with Bremer Financial. In 2018, each made more than $500,000 — a figure that could grow substantially with a sale. (A third trustee, Charlotte Johnson, does not receive investment-management fees.)

"This scheme has nothing to do with protecting the trust or serving its beneficiaries," the company's lawsuit states. Rather, it is "designed to enhance the trustees' personal wealth and public profile."

The lawsuit also accuses the trustees of violating their fiduciary duties as bank directors by sharing confidential company information with competitors in an unauthorized sales process.

"I think we're on the right side of this," Jeanne Crain, Bremer Financial's CEO since 2016, said in an interview. "We're protecting the independence of this organization as our founder intended. I don't see anything in the industry to say that we should go away."

The trustees have filed a response that argues Bremer Financial's board has "no legitimate basis" for second-guessing the decision to sell, and is merely trying to "embarrass the trustees by impugning their motives."

"If Otto Bremer had wanted this to be about the bank, he would have made Bremer Financial ... the parent organization" of the trust, Lipschultz said in an interview.

"But that's not the way he structured things," Lipschultz added. "Otto Bremer's legacy is the trust, not the bank. The trust is the parent company. It owns the shares and determines what happens to the shares. Things couldn't be any more explicit."

It's a unique situation — no other banking company in the country is majority-owned by a trust. But competitive challenges faced by midsized institutions these days also factor into the dispute, underpinning the trustees' argument for a sale.

The outcome likely will hinge on nuances of trust law and how the phrases "necessary and proper" and "unforeseen circumstances" — both of which feature prominently in the trust's documents as potential justifications for a sale — should be interpreted, particularly in the context of today's banking environment.

But perhaps the biggest question is one that nobody can answer with any certainty: If he were alive today, what would Otto Bremer do?

High stakes

It's an uncomfortably public and high-stakes tussle for a banking company that prides itself on serving its communities without a lot of flash.

Terry McEvoy, a banking analyst with Stephens Inc., notes that only five Midwestern banks with more than $10 billion in assets have been sold over the past decade. He reckons that Bremer Financial could fetch as much as $2.3 billion in a sale.

The dollar signs, along with the unique legal issues, have attracted the attention of Wall Street investment banks, industry hedge funds and big-name Manhattan law firms.

Locally, the dispute between one of the state's largest banks and one of its largest charitable givers has become headline fodder for the Twin Cities' newspapers. It also has sparked an investigation by Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, who regulates charitable trusts in the state. Ellison's oversight power could be a wild card in the entire affair.

At the center of it all is a historically symbiotic relationship between bank and trust that observers say has eroded since around the time the three trustees named themselves co-CEOs in 2014 and gave themselves raises.

In recent years, the trustees have clashed with fellow directors at Bremer Financial over dividend amounts, strategy and other control issues, those familiar with the board say. In filings, the non-trustee directors have accused the trustees of "oppressive behavior" and trying to "bully" them into pursuing a sale.

The trustees say they have the right and obligation to pursue a sale, which could double the trust's asset size, and thus charitable contributions, regardless of what Bremer Financial's board thinks.

One thing the two sides can agree on is that a prolonged conflict could hurt the company's value in ways that are bad for everyone.

Already, uncertainty over the company's future has led some existing clients to take their business elsewhere, and potential new ones to put plans on hold, according to Bremer Financial's lawsuit. Recruiting employees has become more difficult.

"Is it a harder conversation to hire talent? You bet," Crain said. "But the worst thing we could do as an organization is to stand still or be paralyzed" by the situation.

"We worry about it a lot,” said Lipschultz. “But we didn’t sue anybody. The bank and directors initiated the lawsuit. How much time we spend in a dispute that could potentially erode value is up to them.”

Otto Bremer's legacy

Otto Bremer emigrated from his native Germany in 1886, landing in St. Paul. A year later, the then-21-year-old took a job as a bank bookkeeper. He stuck with it, and by 1921 was the institution's president.

When the Great Depression hit, Bremer rescued dozens of small-town banks in the Midwest from failure, sometimes showing up on their doorsteps with satchels of cash to keep them afloat.

By 1933, he owned some 55 banks. Ten years later, he consolidated those banks under the umbrella of the Otto Bremer Co., predecessor to today's Bremer Financial. He created the foundation (now the trust) in 1944 to use the company's profits to bankroll civic projects in towns where he owned a bank.

In 1969, federal tax law changed, giving charitable entities 20 years to divest control of for-profit companies. In 1989, the foundation reorganized with a new ownership structure, selling 80% of the voting shares to employees — who can purchase shares directly, through an employee stock ownership program or for their 401(k)s — while retaining 92% of the "economic" shares, which pay a dividend but have no votes.

The arrangement has worked well over time. And both sides can lay some claim to the moral high ground — which is important in a world where the interests of outside stakeholders, such as communities and employees, get more attention.

Bremer Financial has blossomed into Minnesota's second-biggest banking company, behind U.S. Bancorp. It employs 1,800 people in 80 branches across the upper Midwest — many of them in small towns where the company plays a crucial role as a community leader and funder.

In 2019, net income hit a record $156 million, with a return on equity of 12.98% and a return on assets of 1.22%. The company paid dividends of $80.6 million to the Otto Bremer Trust — more than double 2013 levels.

The trust, meanwhile, boasts just over $1 billion in assets and in 2019 invested $56.8 million in 652 separate organizations across the upper Midwest — everything from youth centers and career-training programs to economic development efforts and community dental clinics.

Even so, the setup is decidedly unusual. No other U.S. bank has an ownership and control structure that's so open to interpretation or raises so many potential questions.

On one hand, it's unheard of for the owner of 92% of anything not to have the latitude to sell that interest. On the other, it's unusual for any bank or other company to be sold in the face of strong opposition from its full board.

"There's certainly not a parallel to this in banking, and if there is one elsewhere, I'm not aware of it," said H. Rodgin Cohen, a senior partner at Sullivan Cromwell, the New York law firm that represents the trust.

How we got here

Last April, Bremer Financial was approached by a "similarly sized regional bank" to discuss a potential merger of equals. Nothing came of the discussions, but the trustees say the potential figures bandied about forced them to re-evaluate how the company is valued on the trust's balance sheet.

In late June they began pressing the rest of the board to seek a cash sale, saying the trust had retained Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, without the full board's knowledge, to engage prospective buyers.

The independent directors instructed the trustees to halt their business with KBW, but agreed to discuss "the possibility" of exploring a sale, according to court filings.

The trustees continued to work with KBW and in July raised the prospect of selling some of the nonvoting shares to a third party if the board wouldn't pursue a sale. Under Bremer Financial's organizing articles, a third party could convert the trust's nonvoting shares into voting shares.

In August, a second, larger institution expressed interest to the trustees in buying Bremer Financial. The board's own financial adviser, JPMorgan Chase, concluded that the company's standalone value was "almost exactly the same" as what could be had in a sale, but with the loss of brand and culture. As a result the board decided against pursuing a deal.

Frustrated, the trustees in October announced the sale of shares to a group of 19 hedge funds, which agreed to buy — and convert to voting shares — enough stock collectively to create a 50.13% majority in favor of a sale.

Those funds, including such well-known names as Castle Creek Capital Partners and Patriot Financial Partners, were offered the shares at a price of $120 each, according to court filings, implying a valuation of the company of about $1.4 billion.

The trustees then called for a special meeting to oust the seven non-trustee directors.

Alarmed, Bremer Financial's board filed suit in a state district court to block the stock sale to the funds and refused to recognize that transaction.

'Unforeseen circumstances'

The trust documents Otto Bremer forged in 1944 state that the trust's stock in the company "may be sold only if, in the opinion of the trustee, it is necessary or proper to do so owing to unforeseen circumstances."

In a court filing, the trustees argue that several unforeseen factors give them an opening to sell the trust's interest in Bremer Financial.

Those factors include the 1969 tax law, an increasingly competitive industry environment for midsized banks, and a marked change in Bremer Financial's market value.

Core to the trustees' argument is that the company has literally become too valuable to remain independent. The trust is required to invest 5% of its assets in community projects, most of which has been funded by bank dividends.

The exploration of the potential merger last spring pegged Bremer Financial's value at around $2 billion, roughly double the "fair market value" the trust had assigned to the company at the end of 2018. Lipschultz said the trust is compelled now to use that higher figure when valuing its portfolio.

While Bremer Financial has doubled its dividend over the last six years, the payout needed to meet the trust's giving requirements at the higher valuation level — likely at least an additional $50 million — would take roughly two-thirds of the company's earnings. That's well above the 40% of earnings paid out by the average bank, said Cohen, the lawyer for the trust.

"The real problem here is that the level of dividends required now starts to clash with regulatory guidance and at the very least will represent a severe constraint" on the company's ability to grow, Cohen said.

The trustees also argue that the changing competitive dynamics of the banking market amount to another unforeseen circumstance. Conventional wisdom holds that midsized banks like Bremer Financial are at a disadvantage in the face of intense pressure from fintech firms and big national players.

Bremer Financial argues that all the talk of unforeseen circumstances is hogwash. Through the Great Recession and other times of economic or regulatory upheaval, the trustees have affirmed in required annual court filings that there were no "unforeseen circumstances," and did the same at the end of 2018. Since the trustees sit on Bremer Financial's board, it is disingenuous for them to claim surprise at the industry's pricing dynamics. And no one is requiring the trustees to suddenly change their valuation method on the company's shares to include a potential acquisition premium.

The board majority also says the competitive concerns are a red herring. The company's record earnings in 2019 are proof that recent strategic moves and investments in digital technology are paying off.

The only unforeseen circumstance at play, Bremer Financial argues, is the realization by trustees that a sale would enrich them personally — a charge the trustees vigorously deny.

Now what?

What happens next is anyone's guess, but someone — most likely a judge — will have to decide: Does the bank exist to serve the trust? Or is it the other way around? What did Otto Bremer intend?

Both sides sound confident, and no one sees much room for compromise. Aaron Dorfman, CEO of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, a watchdog group that has been critical of the management structure and pay practices at the Otto Bremer Trust, says it's a tough call.

"It may be better for the trust and its grant-making responsibilities to sell," Dorfman said. "But you have to balance that with the value of the bank to local communities and the consequences of potentially losing that through a sale.

"There are strong arguments on both sides," he said.

Ellison, the attorney general, potentially has the power to halt a sale in the public interest. He also could allow it, but with conditions, such as removal of the trustees or compensation limits. That could test the trustees' resolve.

"He could say, 'If this is truly about the trust, then step down or accept lower pay,' " Dorfman said.

If Bremer Financial were to go on the block, interest could be tempered by the legal battle.

"It's like a family fight. They tend to be messy and play out in high-drama fashion," said Michael DeVaughn, a business professor at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul who studies community banking. "No bank wants buy into that kind of situation."

But in a growth-hungry industry there would certainly be suitors. Bremer Financial boasts a solid base of core funding and a loan-to-deposit ratio of about 81%, with a portfolio dominated by commercial and agriculture loans. About one-third of its business is in the Twin Cities.

That could be attractive to superregionals like Fifth Third and Huntington looking for a foothold in a healthy new market. BMO Harris, Old National Bank and Associated Banc-Corp already operate in the area, and could capture cost savings from a deal.

"I've always thought Bremer Financial would stay independent forever because of its ownership structure," McEvoy said.

"Now we're seeing that nothing is forever in banking. Things can change on a dime."