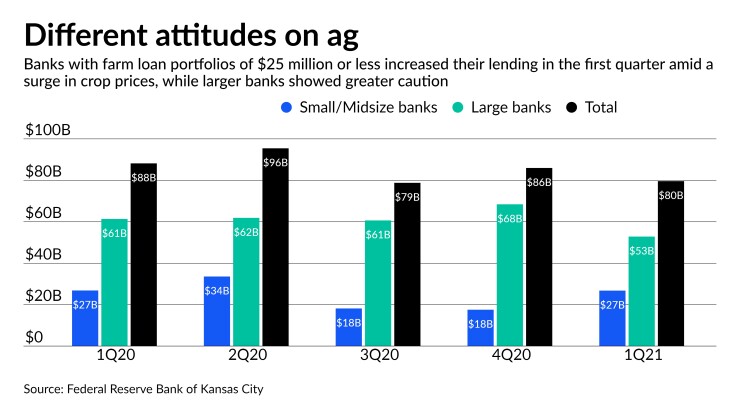

Any farmer looking to borrow more as a result of this year’s rally in crop prices may have better luck with a loan from a smaller agriculture bank than a larger lender.

The recent surge in the prices of crops like corn and soybeans

Agricultural lenders with bigger books, by contrast, had an estimated 22% decline in new loans during the quarter from the previous three months. Even so, the thawing of credit at smaller lenders has given new options to farmers.

“The small and medium-sized farms are in a position to buy machinery for example, and they haven’t been in this position for several years,” said Michael Langemeier, professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University.

It’s unclear to market experts why smaller lenders have seen such a jump in new loans while larger banks are reporting a decline. But smaller lenders have been extending easier terms, perhaps because they face greater pressure than their larger peers to generate earning assets.

The average loan maturity on debt owned by small or mid-sized banks reached 20 months in the first quarter, up 3.5 months from one year prior and a historic high, according to the Kansas City Fed survey. That’s about four months longer than financing offered by larger banks.

Volumes were flat year-over-year for small ag banks and declined for larger lenders. But more loan growth could come for ag lenders of various sizes as farmers seek to boost their production to take advantage of the higher prices.

Futures prices on corn neared $7.50 a bushel on Tuesday, the highest mark since 2013. That’s up from roughly $5.50 just one month prior and less than $3.50 in August, according to CME Group market data. A severe drought in Brazil has curbed the global supply of corn and increased orders from China for the U.S. crop.

“I do think [farmers] will use the extra dough to leverage more,” said John Blanchfield, principal of Agricultural Banking Advisory Services. “They will pay off their unpaid suppliers, but the idea that they would retire term debt just isn’t in their mindset.”

About 14% of farmers surveyed in March expected to make more machinery investments, which often requires new borrowing, over the next year, according to the Ag Economy Barometer published by Purdue University and CME Group on Tuesday. That figure was up from 6% of those surveyed one year before.

The higher crop prices have already helped ag banks’ bottom lines and led to estimates from the U.S. Department of Agriculture that farms

About 2.58% of ag lenders reported being unprofitable during the fourth quarter of 2020, down from nearly 4% three months prior, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

More than half of the ag banks tracked by the agency reported earnings gains over the quarter.

But some farmers and ag lenders are becoming anxious about the rapid growth in crop prices. Expenses like land rents, feed for livestock and even the price of fertilizer are also climbing.

“It’s a little uncomfortable,” said Doug Johnson, president of the $170 million-asset Commercial State Bank in Wausa, Nebraska. “To a lot of [farmers], this rapid of an increase might not be a good thing.”

Farmers and their banks are also facing difficult decisions about whether to lock in higher prices via investments in futures contracts. The risk is that if prices collapse again, farmers will be on the hook for steep margin calls that must be paid to cover the difference between what they were advanced on the futures contracts and the ultimate price they receive for their crops.

Mark Gold, founder and managing director at the brokerage firm Top Third, which helps farmers hedge crop prices, remembers when corn hit $8 per bushel in July 2008. By the end of the year, prices had been cut in half.

“These markets can turn around on a dime,” Gold said.

Often farmers have lines of credit with their bank to cover any margin calls. But if the surge in prices continues, some banks, especially smaller ones, could grow uncomfortable with the risk.

The outlook for prices is murky at best, said Langemeier at Purdue. One model he reviewed gave a 25% chance of corn prices dropping below $4.50 per bushel by the start of next year. But there’s also a 25% chance that prices will be above $6.50, Langemeier said. That kind of gap makes it difficult to plan bigger investments and may explain some of reluctance by larger lenders to make new loans at this time.

Still, futures contracts indicate that pricing is expected to remain steady for the crops to be delivered later this year and even in early 2022, according to Langemeier.

“Communication is just crucial in this environment,” he said. “You wouldn’t want to discourage a farmer to take advantage of some of those prices.”