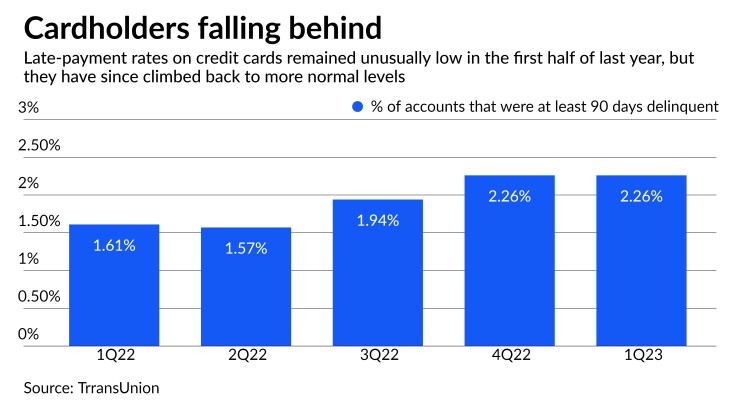

After late-payment rates on consumer loans fell during the pandemic's early stages, lenders spent the last two years waiting for what they called a "normalization."

That return to normalcy is finally here, as delinquencies on credit cards and auto loans have recently either nearly reached or surpassed their pre-pandemic levels. The higher delinquency rates, which typically lead to banks charging off more loans in default, mark an end to a period of exceedingly strong credit performance.

Executives in the consumer lending industry are anticipating that credit metrics will continue to worsen, though they hope the situation will remain manageable even in the event that the economy tips into recession.

Capital One Financial is "assuming some continued pressure on delinquencies and charge-offs" as the economy continues to worsen, a top executive said at a conference Tuesday

"Once you reach those 2019 levels, if things continue to worsen, you can't really say that's normalizing anymore, right?" said Jeff Norris, senior vice president of finance at the McLean, Virginia-based lender. "So I think we're about to drop that word from our vocabulary."

Across the industry, severe delinquencies of at least 90 days on credit cards jumped to 2.26% in the first quarter, surpassing the roughly 2% rate in the first quarter of 2020, according to a report from credit bureau TransUnion. The increase was driven by subprime borrowers, who have been more vulnerable to inflation and interest rate hikes than borrowers with higher credit scores.

U.S. credit card balances are also continuing to rise, jumping to $917 billion in the first quarter from $769 billion in the first quarter of 2022.

That's partly because cardholders are repaying their debt at more normal rates, a shift from earlier in the pandemic, when many consumers used their savings and government stimulus checks to pay off their cards more quickly. But growing balances also reflect a continuing release of pent-up demand after spending options were limited during the pandemic.

"As people are using credit more and just living their lives more, we're seeing balances increase," said Michele Raneri, vice president of U.S. research and consulting at TransUnion.

Rising delinquencies aren't happening just in credit cards. More borrowers are also falling behind on their personal loan and auto loan payments, and delinquency rates in those segments are now above pre-pandemic levels, according to the TransUnion data.

Weaker trends in the once-booming auto sector have

The picture continues to look healthy in mortgages, as homeowners are generally staying current on their payments.

"Homeowners, on average, are in really solid shape," said Warren Kornfeld, senior vice president at Moody's Investors Service. "They've got record amounts of home equity. They have by and large locked in a large part of their housing costs at really low rates."

Renters are faring worse, though, as their cost of living jumps. And if the unemployment rate starts to climb, they will come under more pressure, Kornfeld said.

The job market has held up thus far, with employers continuing to add jobs even as the Federal Reserve looks to cool the economy by raising borrowing costs. The country added 253,000 jobs in April, beating economists' expectations. The 3.4% unemployment rate is the lowest in decades.

Moody's sees a mild recession ahead, with the unemployment rate peaking around 5%. Under that scenario, credit card defaults will likely reach 5% next year, up from 3.5% in 2019, the ratings agency predicts.

"Consumer credit is all about the job market," Kornfeld said, and "we are at a pivot."

Nonbank lenders who specialize in subprime loans have

At JPMorgan Chase, credit card delinquencies of at least 30 days hit 1.68% in the first quarter, up from 1.09% a year earlier. Other big banks reported similar jumps, with credit card delinquency rates climbing to 1.81% at Bank of America and 2.26% at Wells Fargo.

Though subprime borrowers are struggling more, consumers in the aggregate continue to be "remarkably strong," and delinquencies remain "very manageable," Wells Fargo CEO Charlie Scharf said at a conference this month.

"When we talk about things getting worse, it's still from remarkably good levels," Scharf said during a panel discussion at the Milken Institute Global Conference.

So far, the deterioration in consumer credit performance has remained within expectations, according to RBC Capital Markets analyst Jon Arfstrom.

Consumer lenders are "taking a watchful and cautious approach," and they're bumping up their reserves to cover potential loan losses in the event that the economy gets moderately worse, Arfstrom wrote in a research note.

"Overall, we continue to believe credit can perform better than feared given the health of consumer balance sheets and the still low unemployment rate," he wrote.

Still, investors are weighing the possibility that a severe downturn will take a larger toll on lender balance sheets, according to Arfstrom, who wrote that sentiment will likely remain cautious "until signs of stabilization in credit metrics emerge."