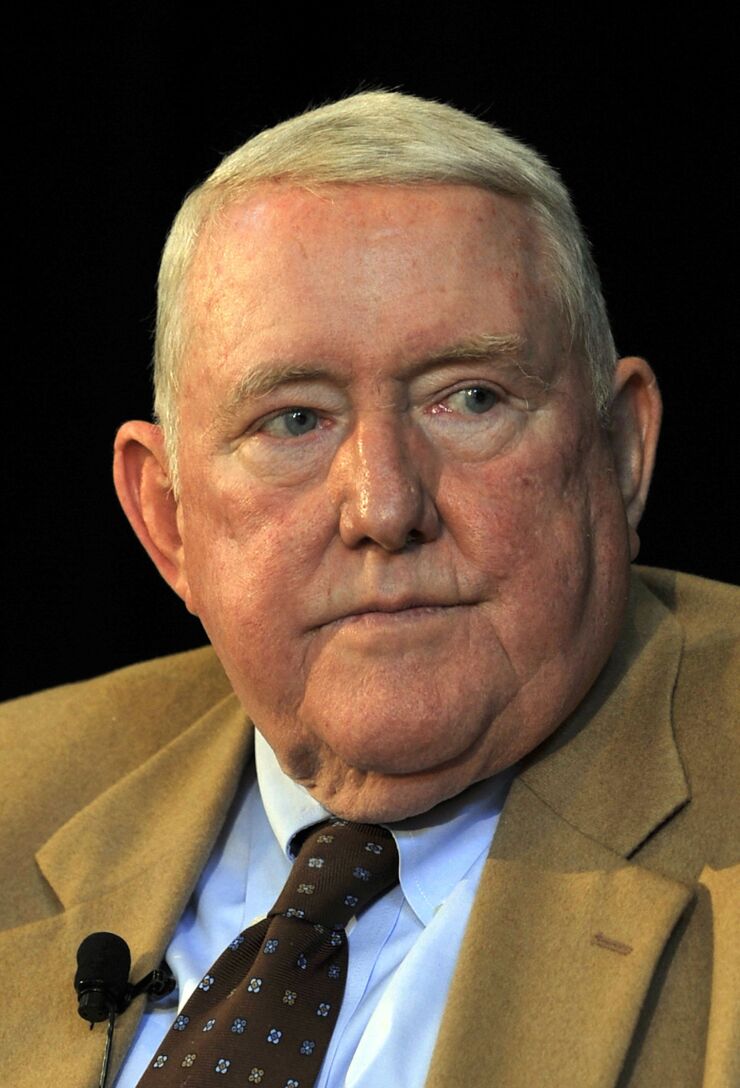

Gerald Corrigan, who spent a quarter century at the Federal Reserve, including an eight-year stint as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, died Tuesday in Boston. He was 80.

After leaving the New York Fed in 1993, Corrigan entered the private sector. He worked more than two decades for Goldman Sachs, retiring in 2016.

Goldman CEO David Solomon called Corrigan “one of the great minds of his day” in global markets and monetary policy.

“He was a person of the highest integrity and a champion of the Goldman Sachs culture,” Solomon said Thursday in a statement to American Banker. “We benefited enormously from his leadership in the global financial community, experience as a central banker, extensive knowledge of the complexities of financial systems and exceptional judgment.”

Corrigan was born in Waterbury, New York, in 1941. He joined the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in 1968, after earning a Ph.D. in economics from Fordham University and teaching there for a year. Corrigan maintained strong ties to Fordham, serving on its board of trustees from 1987 to 1989 and making a $5 million gift in 2007 to endow a professorship in international business and finance.

Corrigan was a protégé of former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker, acting as a trusted troubleshooter on a numbe of occasions during Volcker’s tumultuous tenure, from 1979 to 1987. A 1988 New York Times article called Corrigan “the Fed’s plumber.”

Corrigan helped Volcker tame the Great Inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Volcker also tapped him to deal with fallout from the so-called Silver Thursday in 1980, which stemmed from an attempt by brothers Nelson and Bunker Hunt to corner the silver market.

Corrigan served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis from 1980 to 1984, before taking the helm at 33 Liberty Street. As New York Fed chief, Corrigan was instrumental in dealing with the fallout caused by the demise in 1989 of two major investment banks, Drexel Burnham Lambert and Salomon Brothers. Corrigan also played an instrumental role in the implementation of the Brady Plan in 1989, which helped defuse the Latin American Debt Crisis.

According to Richard Sylla, professor emeritus of economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business, Corrigan’s most impactful moment may have come on Oct. 19, 1987, when he was at the forefront of the response to the “Black Monday” stock market crash, which saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunge nearly 23%.

“My reading of that is Corrigan was the man on the spot,” Sylla said Friday in an interview. “Corrigan was the one who orchestrated adding a great deal of liquidity the brokers who were in real trouble. The Fed acted quickly and told the banks to keep lending to the brokers, the Fed would backstop them. I think that was really Corrigan’s doing." Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan "flew back quickly and took charge, but when the crisis first broke out, Corrigan was the man on the scene. … He made the key decisions very quickly and Greenspan backed him up.”

“That was the biggest one-day crash in U.S. history,” Sylla added. “Corrigan did what a central banker is supposed to do.”

During the 1987 crash, longtime bank lawyer H. Rodgin Cohen of Sullivan & Cromwell was in the office of a client, a bank CEO who wanted to stop lending to one of the big broker-dealers and called Corrigan on speakerphone to explain his decisions to pull his lines of credit.

“Jerry’s response was, ‘Look, you have to do what you think is right for your bank and I can’t order you to lend. But what you do need to remember is that the Federal Reserve’s memory of suggestions that are rejected will be a lot longer than your tenure as CEO.'” The bank CEO continued making credit available to the broker-dealer, said Cohen, who called Corrigan “probably the leading bank regulator not only of his generation but of the last 50 years.”

Gary Stern, who worked with Corrigan at the New York Fed in the early 1970s and succeeded him as president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis in 1985, said Corrigan “thrived on those kinds of challenges.”

“We used to kid around a little bit that he never met a crisis he didn’t like,” Stern said Thursday in an interview. “In the early 1980s … things would come up and any time necessary he would jump on a plane to Washington to meet with Paul Volcker or his Fed colleagues there. It was almost as if he were holding down two jobs. One as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and another as consigliere to Paul Volcker.”

Corrigan performed a similar crisis-management function at Goldman, where then-chairman Lloyd Blankfein chose him to oversee the Business Standards Committee, which was tasked with undertaking a comprehensive review of the bank’s actions during the 2008 financial crisis. Corrigan also served as nonexecutive chairman of Goldman Sachs’ deposit-gathering banks in the United States and United Kingdom.

“I loved him,” Stern, who spent 23 years as president of the Minneapolis Fed, said. “Not only was he the central banker’s central banker, but he was such an engaging and generous guy. He really was.”

Corrigan is survived by his wife, Cathy Minehan, who served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston from 1994 to 2007. He also had two daughters, one stepdaughter, one stepson and five grandchildren.