The fees generated from consumers’ debit card spending have long been a source of acrimony between big banks and retailers. But now the banks have a new adversary: Apple, PayPal and other fresh competitors from the tech industry.

In recent months, banking heavyweights have sought to persuade the Federal Reserve Board to cap the revenue that some tech firms collect from debit cards — a move that would bring those companies under the rules that already apply to larger banks. The campaign sets up a clash between large incumbents and Silicon Valley firms that have been gradually encroaching on the industry’s turf.

“If they are going to act like a bank, they should be regulated like a bank, too,” one big-bank official said in comments that could presage a wider fight over a range of issues.

A tech industry lobbyist, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, fired back at the big banks. “They’re trying to play the victim,” the lobbyist said. “It’s clear that their strategy is to take the shine off of new entrants and new competition.”

Over the last decade, tech giants and smaller fintechs have been inching closer to the banking business. They have typically done so without seeking charters, which would bring certain benefits, but also additional oversight, and could spark a backlash. Banks have generally avoided public spats with the newcomers,

The showdown over debit card fees involves an enormous pot of money — more than $20 billion annually across the banking industry. It offers the big banks an opportunity to fight on favorable terrain, since the tech companies, including some of the most valuable firms in the world, have been taking advantage of a regulatory exemption that was intended to benefit much smaller firms.

While the big banks’ chances of success are unclear, the fight is unfolding as Big Tech’s reputation in Washington is at a low ebb. Both Democrats and Republicans have assailed everything from the tech giants’ monopolistic conduct to their control over personal data and who they allow onto platforms that serve as 21st-century town squares.

“Right now, Big Tech has managed to alienate and have enemies on both the left and the right,” noted Eric Grover, a payments consultant with Intrepid Ventures.

Gaming a two-tiered system

During an earnings call last month, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon pointed to several examples of what he called “unfair competition” by fintech companies.

One item that Dimon cited was the fact that these firms typically are not subject to the price caps on debit interchange fees — which are paid by retailers, and are often called swipe fees — that constrain large banks.

The month before, a JPMorgan executive named Matthew Kane met with Federal Reserve staffers to discuss the same issue, according to a notice that was recently posted on the central bank’s website. Kane was joined by two lawyers from Capital One Financial, as well as Rob Hunter, executive managing director at The Clearing House, the payments company owned by the nation’s largest banks.

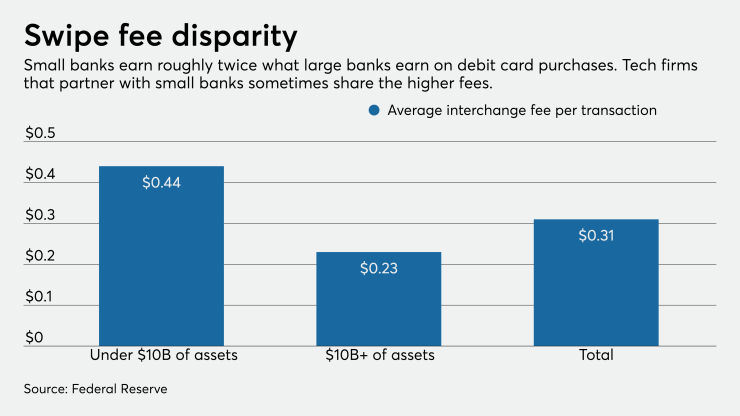

The Dec. 10 meeting focused on decade-old rules that cap the fees that large banks can collect when their customers pay with debit cards. For big banks, those fees are capped at 21 cents, plus 0.05% of the value of the transaction. An exemption for banks with less than $10 billion of assets was included in the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 in an effort to attract more political support for the price caps championed by Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill.

This two-tiered system

The pricing disparity has given rise to scenarios that likely were not envisioned by members of Congress who supported the Durbin Amendment 11 years ago. Over the last decade, various nonbanks, including prepaid card companies, neobanks and tech giants, have partnered with small banks on cards that are not subject to the price cap.

The higher swipe fees have helped support fintechs that otherwise would have generated little revenue, such as the challenger bank Simple, which later saw the fees diminish following its purchase by the Spanish banking giant BBVA,

In another illustration of how critical higher swipe fees can be, Customers Bank in Phoenixville, Pa., which crossed the $10 billion-asset threshold in 2017 and again in 2019, cited the rules as a top reason for

Other small banks that occupy similar niches include the $6.2 billion-asset Bancorp Bank in Wilmington, Del., the $2.8 billion-asset Green Dot Bank in Provo, Utah, and the $780 million-asset Sutton Bank in Attica, Ohio.

“Large fintechs are exploiting loopholes created by a bifurcated regulatory system,” Richard Hunt, the president and CEO of the Consumer Bankers Association, said in an email. “As a result, these large fintechs with tens of billions in assets are playing by rules created for small community banks.”

Big banks strike back

The big banks fleshed out their argument in an October letter to the Fed.

Rather than simply looking at the asset size of the card-issuing bank, the Fed should take into account the combined asset size of the bank and its tech partner, the Clearing House contended

PayPal, which currently partners with Bancorp Bank on both the PayPal Cash Mastercard and the Venmo Debit Card, reported $70 billion of total assets at the end of 2020.

Apple, which has $354 billion of total assets, partners with Green Dot Bank on Apple Cash. That product allows iPhone users to make purchases from a mobile wallet.

In October, Apple CEO Tim Cook said that the iPhone maker is “very bullish” about the payments business and sees opportunities to expand further in that sector. “The U.S. has been lagging a bit in contactless payment, and I think that the pandemic may well put the U.S. on a different trajectory,” Cook said during an earnings call.

Spokespeople for PayPal and Apple did not respond to requests for comment for this article. A Fed spokesperson declined to comment on the big banks’ proposal.

Google may also be drawn into the fight, though checking accounts under development by the Mountain View, Calif.-based search giant are expected to be offered in partnership with

Beyond the tech giants, the big banks’ push to revisit swipe fee rules has potential implications for a range of fast-growing tech firms, including the payment processor Square, the embattled trading app maker Robinhood and the challenger bank Chime, all of which offer debit cards in partnerships with small banks.

The Clearing House argues that in order to qualify for the exemption from debit price caps, the Fed should require all customer deposits to be held at the partner bank. That would be at odds with how these arrangements typically operate, with a large bulk of customer funds usually held in a corporate account at another bank.

The upshot is that if the Fed were to embrace the big banks’ proposal, the partnerships between many tech companies and small banks would likely become harder to manage and perhaps untenable in some cases.

“Any action that alters the business model this significantly,” Sarah Grotta, a debit payments expert at Mercator Advisory Group, wrote in a recent blog post, “will have consequences for the market.”

The Clearing House said in a written statement that it supports the exemption in the debit card fee rules for banks with less than $10 billion of assets. “It was intended to protect small banks that may not enjoy the economies of scale of large issuers. It was not intended to be used by large fintechs to game the system,” the statement read.

The big bank-owned payments firm also said that under its proposal, small community banks would still be able to receive the higher swipe fees for their own debit-card programs and those of partners with assets of less than $10 billion. It noted that the vast majority of small banks would not be affected by the plan.

The Clearing House wants the Fed to make changes without going through a rulemaking process that includes an opportunity for public comment. That would be a mistake, said Ben Jackson, chief operating officer of the Innovative Payments Association, an industry group whose members include large banks, prepaid card companies and small banks that specialize in partnerships with fintechs.

“If the Fed does consider this, we’d hope that it seeks input from a broad range of companies in the payments industry,” Jackson said.

“We should be scared”

The big banks’ decision to take a tough stance on Big Tech’s use of a regulatory loophole likely reflects a confluence of factors. First, large tech companies have some key advantages in the financial services realm, including huge customer bases, modern infrastructure and enormous financial wherewithal, which pose a peril to the big banks.

When JPMorgan's Dimon spoke last month, he hardly sought to downplay the competitive threat posed by Apple, Google, PayPal and other industry behemoths. “Absolutely we should be scared shitless,” he said during JPMorgan’s most recent earnings call.

Targeting the tech industry also gives the large banks an opportunity to play offense in the long-running swipe-fee wars, rather than just responding to

In the coming years, large banks are likely to tangle with the tech industry on a number of fronts. Those topics include

Another looming issue is whether the large tech platforms should be required to provide better access to the vast amount of customer data they hold. Such a move could help banks by giving them more data to use in evaluating loan applications. A House subcommittee report last year

Attitudes in the banking industry about the threat posed by tech-driven innovators have ebbed and flowed over the last several years, said Mark Twerdok, a partner at KPMG.

“The fintechs scared the banks,” he said. “And then the banks kind of jumped into bed with them.”

“I think maybe that pendulum is starting to swing again.”