The Future of Checks – Tales From The Crypt

Halloween is approaching, so we might as well talk about death. Checks are dying and about to die quicker, given the rise of instant payments. In the next two years, many banks will have strategic plans to phase checks out, given their cost and reduction in frequency. Checks are getting to the point where they are too costly to process for the bank, business, and household. What will banks do with their checking accounts in a world without checks? This article breaks down the check’s demise, its timing and forecasts what happens next.

A Quick History of Checks

While checks have been around since Roman times, the processing of checks has always been slow and expensive. This is why when the US banking system was founded, John Hancock and his contemporaries only used checks for large transfers. Checks were written in various forms, on different paper stock, and it was up to banks to largely settle (clear) checks on their own as it was faster than going through the Federal Reserve. The process took weeks and sometimes months to move and settle checks between various banks.

After World War II, checks were the hot payment technology and helped fuel the economic boom that followed. Checking accounts in the U.S. doubled between 1939 and 1952, rising to 47 million. The number of checks written hit about 8 billion in 1952 and the amount per check dropped. At its height, checks accounted for 86% of all payments in the U.S. Banks struggled with the cost of processing all those checks.

By 1961, the Federal Reserve built out its infrastructure and started clearing checks at 47 processing centers nationwide. Banks would sort and bundle checks, then deliver them to these centers where the Fed would reconcile and deliver the check to the bank the check was drawn on. Each bank would then check signatures and pay the payee’s bank. The process was sped up by technology and legislation in the 70’s and 80’s so checks could be scanned and presented faster, but the process remained costly. On average, it took about 17% of a bank’s staff to deal with check processing alone.

By the early to mid-90s, ACH, both credit and debit, started to increase in popularity, especially for businesses. The rise of card-not-present transactions for phone and then e-commerce, starting in 1994, cannibalized check volume, as did Paypal, retail ACH for phone and internet transactions in 1998. The debit card started to rise in popularity in 2004, as did an explosion of ATMs in 2005, affording the general population more access to cash. From there, checks steadily declined.

The banking industry, pushed by the events of 9/11, moved to check imaging by the Check 21 Act in 2003. Now, a paper check could be scanned and turned into an electronic payment. This was a huge boost in efficiency and helped offset some of the incremental cost increases caused by steady check volume declines. Still, despite the imaging, many banks, for a time (and some do to this day), printed the image replacement document (IRD) and put them into the customer statement via mail. As such, it took years before total efficiency could be realized.

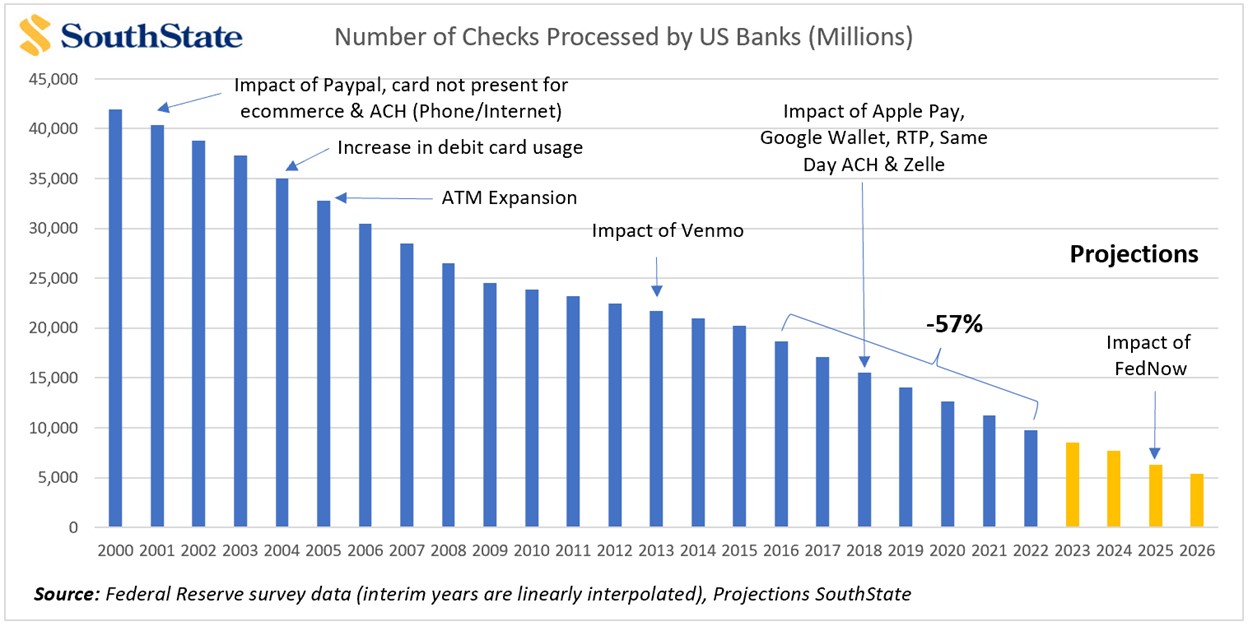

However, volume has steadily declined as Venmo gained more traction by 2013, combined with real-time payments, Apple Pay, Google Wallet, and Zelle after 2017. Over the last ten years, from 2012 to 2022, checks by volume have declined some 57%.

With the strong expected growth in instant payments from FedNow and the widespread adoption of Request for Payment by The Clearing House, checks are expected to suffer another material decline in 2025 as traction increases.

The Problem with Check Processing – Bank Perspective

From the bank perspective, check processing takes labor and fixed asset expenses in the form of branches and an ATM network. While this number varies widely by banks, on average, we estimate that about 15% of the fixed branch and ATM costs, plus the support staff, should be allocated to check handling based on time-on-task. This cost includes receiving checks, scanning, providing checks, check security, data verification, check data management, compliance, fraud management, customer service for transactions, handling complaints, dispute resolution, and exception handling.

Aside from the logistical and compliance problem of check processing, the payment channel is fraught with other problems even in its imaged state. The payee’s name and address appear on their checks, as do their bank account number and signature for the world to see. This is an improvement from the 1980s when checks also included a customer’s social security number and driver’s license, but the fact remains that checks are not secure and provide too much information, making it easy to commit fraud. Any criminal can steal, forge, or alter a check almost at will. The whole payment chain is at risk once a check leaves the payee’s hands.

There is also the fact that checks are usually offered to 100% of a bank’s customers usually without amount or frequency limits. That aspect presents some unique vulnerabilities for checks compared to electronic payments, where not every customer qualifies and those that do have transaction and daily limits.

In addition to the logistics of check clearing and the availability of fraud, settlement is no easy feat. On average, it takes three to ten days to clear a check, and checking accounts can have insufficient funds; the checks can be canceled or delayed in their delivery. The handling and reconciliation process is costly and takes time. Further, check problems are often handled in the branch or via phone, which are also costly service channels.

The Cost of Checking

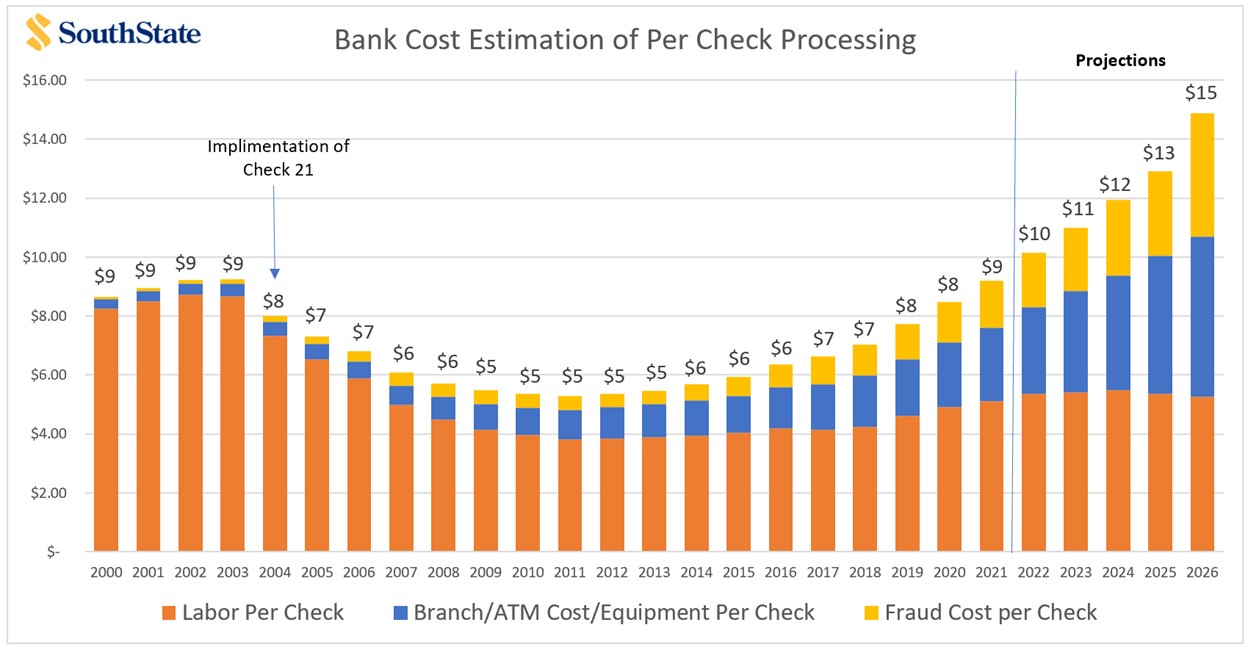

Of course, as checks decline, the incremental cost increases. Take the direct and indirect cost to manage a check from the banking perspective and divide that by the total number of checks per year as detailed above, and you have the graphic below detailing the recent history of a cost per check.

As of the end of last year, Banks paid about $4 in labor per check and about $6 in fraud costs. Add to that about $8 of funds transfer pricing costs from the branch, ATM, lockbox, and check equipment, and banks have an approximate cost of about $10 to handle a check. That is an expensive item.

As check volumes continue to decline as instant payments take hold and fraud increases, we predict the cost per check will hit over $15 per check by 2026. This is the Rubicon in check processing. At this point, checks become almost cost-prohibited.

We predict that banks will realize this at the end of 2024 and become more proactive in moving their customers off checks and onto ACH and instant payments.

The Problem with Check Processing – Customer Perspective

The future of checks doesn’t look good from the customer’s perspective either. Consider a recent Yahoo survey where 45% of Americans responded that they did not write a single check last year. If you are under 34, writing a check is rare unless it is through bill pay.

Households and merchants must receive, verify, manage, transport, secure check stock, and deposit checks. Many customers use a lockbox arrangement, further increasing costs and adding reconciliation challenges. Households and merchants also have a certain amount of fraud risk, both providing and receiving checks. According to the 2022 AFP Payments Fraud and Control Survey, 66% of organizations were victims of check fraud.

The business needs to manage its liquidity and reconcile which checks are outstanding and which checks are cleared.

To the business, the cost is about $4 to $25 per check, depending on the volume and infrastructure. An estimate from the Wall Street Journal puts the average cost of managing checks for a business at approximately $25,000 per year in check materials, labor, postage, bank charges, and management.

Why do businesses still put up with this cost? The answer is a combination of tradition, ease of use, and, in many cases, putting a check in an envelope with an invoice or receipt is still the easiest way to manage payment and reconcile a transaction. Almost half of household payments and about 75% of small business expenses are paid by check.

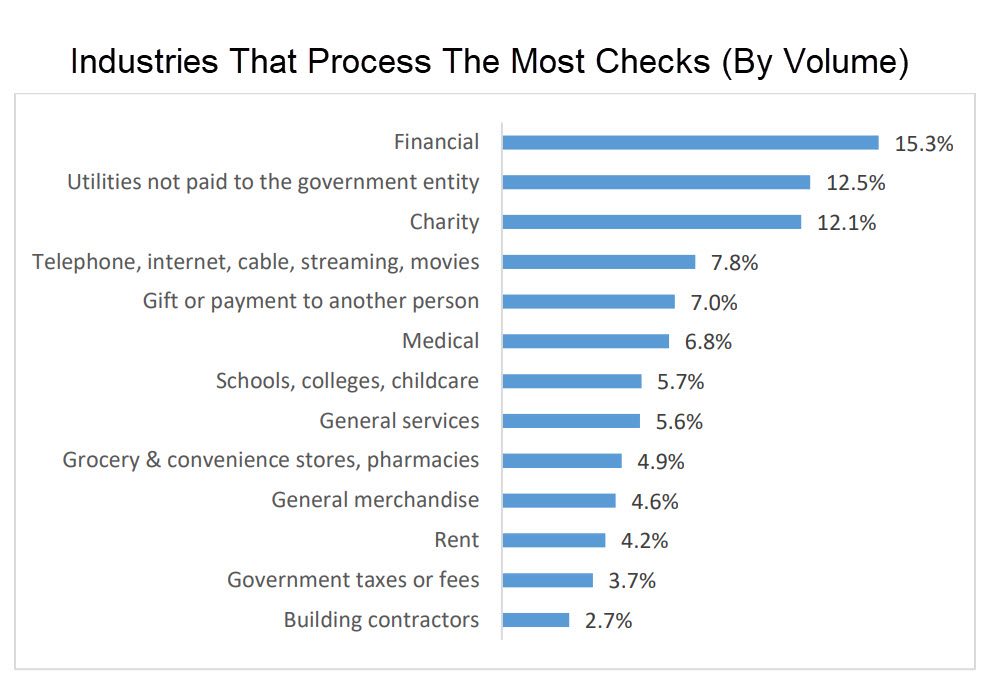

Next to financial institutions, utilities, and non-profit organizations are the largest handlers of checks and could benefit the most from moving to electronic payments. Below are the largest industries that use checks according to the Federal Reserve based on the number of items. Unsurprisingly, both these industries are being hyper-targeted to leverage the Request-for-Payment (RfP) functionality and will likely migrate faster than most other industries. Healthcare, schools, landlords, and homeowners associations are not far behind.

The Rise of Instant Payments

As we detailed HERE, instant payments have a number of advantages outside of allowing households and businesses to send and receive a payment 24/7/365. This complements other 24/7 bank payment channels, such as debit, credit, and ATMs operating 24/7/365.

The ability to schedule a payment, lower fraud, and risk incidences, electronically package both the payment and invoice/receipt, and always have a reconciled account will change how households and businesses make payments. This will have a dramatic impact on the future of checks.

By 2026, we predict instant payments will largely displace checks in their many forms. Checks will become too costly for the household, business, and bank to process.

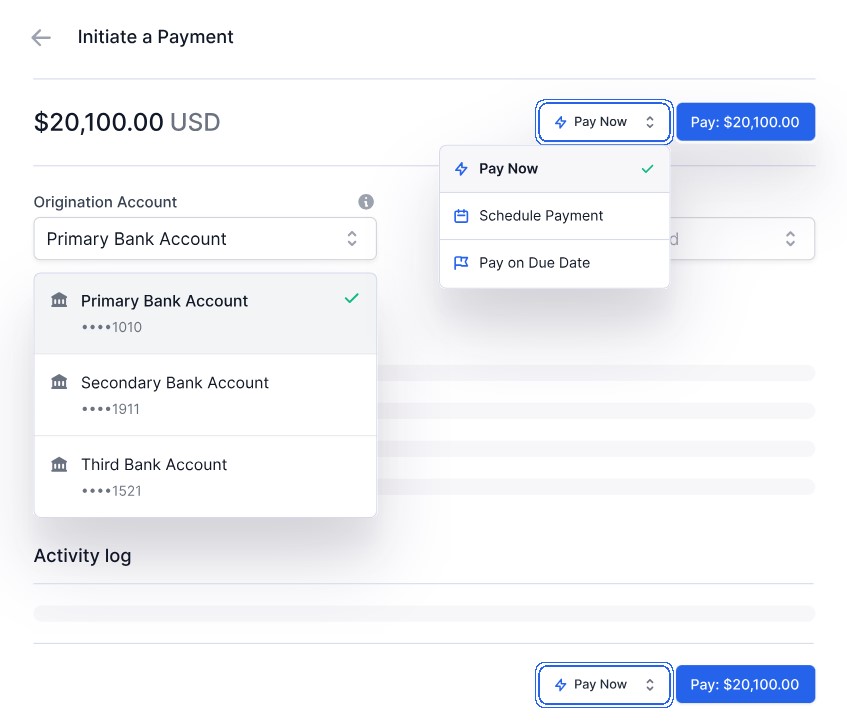

Part of this expected increase in electronic payment usage stems from the current trend of embedded finance. National and many community banks want to integrate into the accounting and enterprise resource planning (ERP) software (example below). This is a game changer for small and mid-sized businesses as it allows a company to send or receive payments from their core system without manually entering the information in two places and going into a banking application. This saves a business approximately 15 minutes per payment, a material improvement in accounting efficiency.

Getting Ahead of the Future of Checks

Every management team should have a strategic discussion around the systemic changes associated with the future of checks. Thinking through how to turn a checking account into a transaction account is critical to the longevity of a bank. As more and more households, small businesses, non-profits, government agencies, and corporations move away from checks, then wires cash and debit cards, banks that don’t offer instant payment solutions in place of checks will be at a disadvantage.

The profitability of many accounts is tied to transaction volume. The more transactions, the more fees, and the higher non-interest balances are usually held. Without a modern payment offering, banks will have to place more emphasis on rate to attract funds, placing them at a disadvantage. In addition, checks and other associated payment channels, such as debit with its interchange, generate a wide array of fees that will continue to be cannibalized.

Worst of all is the fact that it is not the set of payment tools that will become important but the vast array of new products that will be built on top of the payment tools. With a flexible payment platform, banks can offer various new products like scheduled payments, escrow accounts, split payments, virtual accounts, disbursements, and more.

There are many choices out there, and our upcoming instant payment product release early next year, Called Pay Command, is just one of many. This will include FedNow, The Clearing House, and the ability to act as your funding or settlement agent so you don’t have to manage the channel 24/7/365. If you are a financial institution, to sign up to learn more and get notified of product updates, click the link below.