Executive Summary

- Central banks and regulators around the world know climate risk constitutes a growing risk to financial stability. In their role to enable, manage and supervise financial sector (FS) participants in dealing with environmental risks, a number of them have focused on several crucial areas.

- Many, however, have been less proactive. They should consider the following as priorities:

-

- At a minimum, ensure they have a clear overarching strategy and framework that is relevant to that country’s climate change requirements, with a consistent operating model across departments, each of which has its own KPIs.

- Incorporate climate change factors into their policies, create awareness internally of their climate change strategy, and ensure that staff have the required skills and access to dedicated resources.

- Increase awareness among FS participants on the importance of climate-positive initiatives and how those affect them.

- Ensure their supervision departments check that banks incorporate aspects of climate change into their business models where relevant (even though it’s not their role to change such models) – for example, as regards climate risk.

- Take a position on how they can motivate banks to support the financing of a greener economy – for example:

- Devise guidelines requiring that banks allocate a minimum percentage of loans to green initiatives or to sectors like renewable energy.

- Offer discounted loans to banks to incentivise them to lend to climate-positive organisations.

- Amend their reserves policies so the sums that banks must keep with the central bank are contingent on how much they lend to, say, renewable energy projects.

- Consider how banks might factor environmental risks into their capital adequacy ratio calculations.

- Consider setting up a climate change-related toolbox that can be shared with banks as a ready reckoner.

- Consider issuing increased volumes of green bonds – and, in terms of public sector purchases, focus on buying more green bonds than traditional bonds, for example.

- Ensure that central banks’ investment programmes and funds focus on climate change and green projects – with those fund managers acting as ambassadors for responsible investing, and considering environmental factors when making decisions.

Overcoming the challenges

- Decarbonisation is a key challenge for the FS sector – as is how to fund the vast sums needed to transition to clean energy by 2050. Another is how to measure the effectiveness and impact of policies, guidelines and regulations – which the lack of real-time data hampers (for instance, calculating the exposure of the FS sector to climate risks).

- What’s needed are standardisation and an accepted green taxonomy, both of which would also help investors.

- That said, banks already carry a heavy compliance and reporting burden, so central banks and regulators must consider how to balance a carrot versus stick approach.

- Banks in the Middle East will eventually need to incorporate these requirements into their business models, policies and compliance/risk management frameworks; those that don’t could find themselves disadvantaged as clients shift to banks that are proactive. That said, banks in the Middle East should regard incorporating such requirements as an opportunity, not a threat.

Carrots, sticks, data

- A successful approach will likely involve a mix of compulsory and voluntary measures. In all cases, it will also require using data and analytics, automation and technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

- Central banks and regulators should also raise awareness of climate risks and solutions, which will include elements to motivate positive actions.

- Driving behavioural change in the FS sector requires a well-designed, holistic programme and focus – aspects that Accenture has worked to deliver for central banks, regulators and the broader banking sector, including in Middle Eastern countries like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, where this subject is gaining importance.

- As a leader in this space, we have supported our FS clients to define and implement their strategies on this topic and ensure they are being followed.

A) Climate risk is financial risk

Sustainability in finance has become increasingly important, with growing debate about the role that regulators, central banks and banks should play in promoting it.

The term “sustainability” can cover a wide spectrum that encompasses environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. From a finance perspective, it has to date focused mainly on climate change, the key challenge of our era. The decade from 2010-2019 was the warmest in recorded history,[1] and 2020 equaled 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded.[2]

This focus on the climate aspect of sustainability is therefore understandable, and is what we will focus on. Various central banks have been vocal about the risks that climate change poses to financial stability – the European Central Bank (ECB), for example, states that these risks “have the potential to become systemic, in particular if markets are not pricing the risks correctly”.[3]

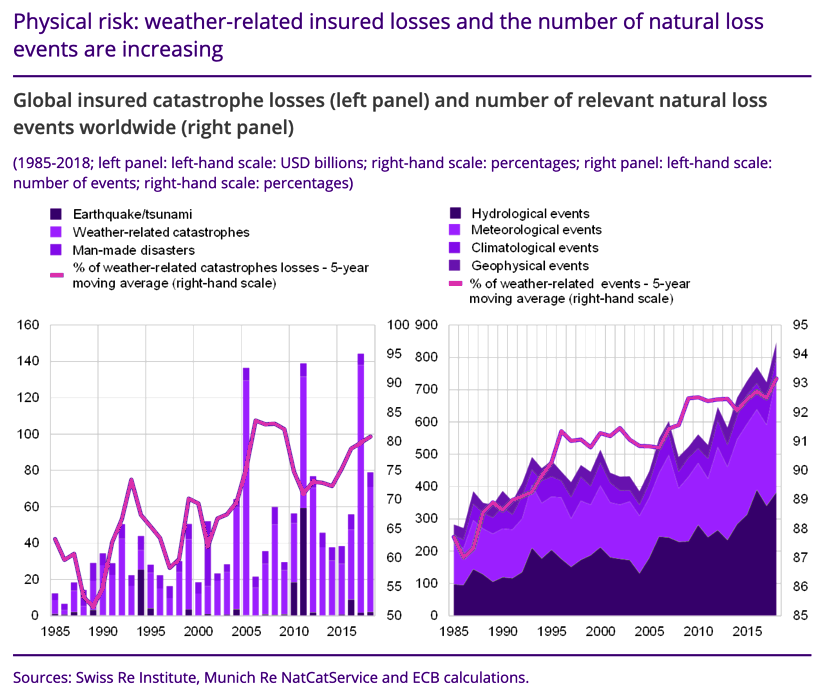

That is no small matter: as the chart below shows,[4] the share of weather-related catastrophe losses has risen steadily in recent decades, as has the frequency of weather-related loss events.

Climate risk is financial risk: weather-related insurance losses are on the rise – as is their frequency. (Source: ECB)

Such consequences explain why prudential regulators like the European Banking Authority (EBA) are taking the impact of climate change seriously. The EBA, which manages the two-yearly stress tests for banks in the EU, is reportedly developing a dedicated test to determine the vulnerability of banks to climate change risk.[5] The chances are high that other regulators will do the same – in this region, as elsewhere: in 2021, for example, the energy minister of Saudi Arabia said the country aimed to do more even than most European nations to tackle climate change.[6]

Red flags, green lights?

Many regulators are already thinking hard about climate change and risk factors – the Bank of England (BoE), the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS)[7] are just three that come to mind. Regulators today appreciate that banks will “inevitably be affected” by climate change events, which is why the likes of the HKMA have said they are now focused primarily on the risks that climate change poses to banks.[8]

The risks of climate change, and the need for action, are understood on a political level too – in the Middle East as much as anywhere. Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, for example, has said that “to preserve the unique environmental character of the region, environmental sustainability laws and mechanisms will be developed”.[9]

The consequences of climate change explain the high level of understanding globally of the need to act. That has helped to update and align prudential programmes such as capital requirements under Basel III, and resulted in a consistent framework for key tools.

Prominent among these is the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework, which improves how climate-related risk is assessed and reported.[10] Another is the Equator Principles, a risk-management framework to assess environmental and social risk in projects, and to which some banks in the UAE already subscribe.[11]

The importance of the subject of climate was heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a massive drop in travel and a worldwide economic slowdown. Both of those resulted in lower emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and show what might be necessary in terms of mitigating the effects of climate change.

While those changes were temporary, they have raised questions for regulators and banks about the best actions. Some courses of action could logically flow from the UN’s outlining of six areas for governments to act as they rebuild their economies:[12]

- Green transition: accelerate the decarbonisation of economies

- Promote green jobs, and sustainable and inclusive growth

- Build a green economy by making people more resilient – and with fairness as a central tenet

- Invest in sustainable solutions, end subsidies for fossil fuels and ensure polluters pay

- Tackle climate risks

- Cooperate with other nations

Decarbonisation is a particular challenge for financial services, and at its heart involves making investments into the fossil fuel industry less attractive. However, that doesn’t seem to be happening, at least not in many geographies.

A related challenge is funding the vast sums required to transition to clean energy by 2050: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has calculated it would cost US$51-122 trillion in energy investments if the world is to reach net-zero emissions of CO2 by 2050 to meet the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.[13]

ESG: The regulatory push

On the ESG level more generally, the global trend is towards greater regulatory focus. In the EU, for example, the European Banking Authority (EBA) released a consultation paper to industry that discusses increasing ESG incorporation in the regulatory framework.

Globally, the debate is about the focus regulators should take: “single materiality”, which is favoured by the US and which targets financial impact; and “dual materiality”, which is an EU preference and which targets financial and non-financial impacts.

However, as is clear, the climate is ahead of its S and G cousins in many jurisdictions in the ESG space. That’s in part due to a lack of globally agreed principles on social and governance issues, which matters because the principles that are in place tend to be motivated by local factors. This makes it hard for regulated banks, which are typically global and systemically important, to factor them into their prudential frameworks.

Yet although the global consensus on the need to address climate change is better developed, there are still challenges. The EBA, for instance, is discussing how best to deal with determining climate risk given a lack of data quality and availability, and is consequently assessing proxies that could act as substitutes. And in the Middle East, the Arab Monetary Fund has called on central banks to adopt “a comprehensive governance framework in managing natural disasters and ramifications of climate change and addressing the potential impact”.[14]

Additionally, coming up with solutions isn’t just about resolving such practical challenges; there are often political factors to overcome too.

In other words, the regulatory domain for ESG remains relatively undeveloped, and even this narrower climate area lacks sufficient regulatory coherence. And yet the conversations that will shape the outcomes are well underway, with the sector talking far more about sustainability. That said, sustainability is more mature in other industries and other parts of the financial services industry like asset management – as BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s annual letter to CEOs makes clear.[15]

Our view is that banks must do more. And this raises the question: How best can this be achieved? One example is by further leveraging their use of data. By applying AI, machine learning and other technologies to gather and process data in real-time and near-real-time, banks can convert this valuable and under-used resource into insights and actions.

However, that’s not the only path open to them – as we shall see.

B) The regulatory hand: Carrot or stick?

A core task for central banks and regulators is to decide how to develop policies that incentivise financial markets to allocate capital towards more sustainable, climate-positive investments.

Central banks and regulators have a crucial role in driving this change, and numerous tools to help them do so. First and foremost, though, they need to ensure that they craft an overarching strategy and framework that meets the climate change requirements that their country has outlined. And central banks and regulators must also incorporate climate change factors into their policies.

In addition, they need a clear action plan – a climate-related strategy with KPIs, and with a consistent operating model applied across departments, be they supervision, investment, research and the like, and each with their own KPIs.

Linked to that, central banks and regulators should focus initially on raising awareness of their action plan internally, and ensure that their staff have the requisite skills and access to dedicated resources that are necessary for its success. After all, if central banks and regulators are looking to drive improvements externally, they need to show they are doing so internally too.

Central banks can also effect change in how they guide banks and the broader FS sector to boost awareness of sustainable finance and the importance of lending to climate-positive initiatives, and encourage the flow of capital to green assets. With the IPCC noting the vast sums needed, as we saw earlier, that could have a big impact.

And whether that guidance is made voluntary or as part of a framework, it can provide a strong signal. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC), for example, and the China Banking Regulatory Commission together developed the Green Credit Guidelines, a framework that requires banks to set up a system that monitors and evaluates green credit.[16]

The Middle East has taken some important steps. The UAE, for instance, introduced legislation in 2018 to help develop its primary and secondary green financial markets.[17] That came as Dubai seeks to become the regional green finance hub, a role that includes establishing mechanisms with which to fund green projects – as the government-backed Dubai Green Fund does.[18]

Although China is ahead of most countries, some of the biggest nations have acted – for example, the Green Finance Study Group, which the G20 launched in 2016 to assess the need for green finance to scale up, and the challenges this would bring.[19] Among its recommendations are that authorities devise policies and frameworks for green finance, improve how such activities are measured, and work with the private sector to create voluntary green finance principles.

Inevitably, the multitude of efforts to promote positive climate change raises the question as to whether central banks and regulators should take a carrot or stick approach in trying to ensure banks act in a more climate-friendly manner.

In our view, a carrot approach might be better from a central bank’s perspective – say, for example, easing capital requirements for lending that favours climate change initiatives (though this would require deciding whether the risk on such loans is in practice lower).

Central banks can also look to influence behaviour by, for example, issuing green bonds (as some, like Hong Kong,[20] have done and as others are contemplating) with proceeds available only to finance green projects. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), for instance, recently launched its second green bond fund for banks, with the funds promoting green finance by investing in climate-friendly projects like renewable energy.[21]

Additionally, they should take a position on the many ways in which they can motivate banks to support the financing of a greener economy – and in this, there is no shortage of tools to hand. For example, central banks and regulators could look to enforce compliance by requiring that a certain minimum portion of a bank’s portfolio be focused on climate issues.

They can also de-incentivise money flows into fossil fuel firms or assets that have a high carbon footprint, and they can encourage investors in corporate bonds to focus on buying the instruments of firms that support climate-positive actions.

Other possible steps include:

- Devise guidelines that require that banks allocate a minimum percentage of loans to green initiatives or to sectors like renewable energy, and encourage asset managers to allocate capital with increased sensitivity to this topic

- Offer discounted loans to banks to encourage them to lend to climate-positive organisations

- Require that banks factor environmental risks into their capital adequacy ratio calculations in the same way that they factor in critical checks like KYC and anti-money laundering; indeed, climate-change data should be just as commonly included

- Work with the broader FS sector to consider new technologies that are green, and that therefore reduce carbon emissions, but which at the same time don’t impose an operational burden on banks. Examples include discussing with the sector the subject of green IT, and supporting topics around migrating IT functions to the cloud

Central banks and regulators can also reduce subsidies and incentives for organisations that increase their carbon footprint significantly, and they can look at how to invest their own assets more responsibly as, for example, France and Finland’s central banks are doing.[22]

Additionally, they could highlight to industry – and certainly should consider doing so – the added value brought by supporting climate-positive initiatives, chief among which are changing customer preferences. In an environment where financial institutions are increasingly frustrated by the impact of regulatory requirements on costs and profitability, that would likely be a better approach in some jurisdictions. Central banks could, for instance, advise banks on topics like how to devise and issue new green products (including working to ensure regulatory approval for such products) that would both offer new revenue pools for banks and provide a competitive advantage.

A further area for consideration involves supervision departments. Even though it’s not their role to change banks’ business models, these departments could be instructed to check that banks have incorporated aspects of climate change into those models – for example, ensuring that they’ve calculated the impact of climate risk-on assets.

Promoting vs enforcing

While it’s clear that central banks and regulators have an important role to play in promoting positive climate change initiatives in the banking sector, it’s less clear whether that role extends to enforcing it. Going back to the point mentioned previously, regulatory and compliance costs are a growing burden on the financial system, which is why it’s key that – whether they are promoting or enforcing such initiatives – regulators do so in an automated, efficient manner.

The ECB and climate change

The ECB, which is in the vanguard of sustainable finance efforts and which views climate change as a systemic risk to the financial system, is concerned that too much funding is going into carbon-intensive sectors.

In 2020, it said it would consider making changes to its operations to help combat climate change, and was prepared to use its €2.8tn asset purchase scheme to achieve its green goals.[23]

The ECB already factors sustainability into its market operations, and in particular into its bond purchase programmes. In 2020, it also announced it would accept sustainability-linked bonds as collateral in its asset purchase programs from 2021.[24]

Additionally, in its efforts to address potential market failure, the ECB is considering adapting its market neutrality rule to favour green assets.[25]

But in both cases, the challenge for regulators and central banks is finding ways to measure how successful their policies are in promoting or enforcing finance that underpins climate change initiatives – with the caveat that it’s easier to do so with compulsory measures than with voluntary guidelines.

Success also requires looking ahead to calculate how much regulators can pressurise the banking system on climate change initiatives in the future while also ensuring financial stability through the coming transformations.

Finally, in all of this – as we’ve seen around the world – collaboration is important, with the Network on Greening the Financial System (NGFS) a leading exemplar.[26]

Data (front and) centre

Data, of course, is central to the actions that regulators and central banks should take, as are the relevant processes and technology required to harvest and interpret that data. We’ve written extensively about that previously – starting with this article[27] – but briefly, the premise is that central banks need to become digital regulators. Doing so successfully requires focusing on four pillars:

- Pillar 1: Harness the power of data to sharpen their surveillance of risks, strengthen their financial oversight, drive regulatory compliance, and boost monetary and financial policy-making[28]

- Pillar 2: Enable and drive innovation internally and externally to promote a vibrant digital economy[29]

- Pillar 3: Drive efficiencies and develop a secure, resilient, future-ready infrastructure for both the central bank and the financial services sector[30]

- Pillar 4: Improve communication and engagement with the industry using more holistic digital services and two-way communications[31]

Underpinning those pillars is a foundation that consists of transforming central banks’ workforces for a digital future, strengthening internal delivery capabilities in terms of robust operations, like leveraging automation and using lean processes, and helping to transition the workforce of the broader financial sector.[32]

Operating as a digital regulator will vastly improve how central banks and regulators can measure the risks associated with not driving positive climate change initiatives. It will also help them track compliance both with compulsory measures and voluntary guidelines. In that way, central banks and regulators will be able to determine where individual banks stand with respect to their peers and know in real-time which efforts are bearing fruit.

D) Looking ahead

Climate risk is a crucial global issue, with potentially profound impacts on the stability of banks and the broader financial sector – to say nothing about its effects on societies more generally.

Although it’s an issue that is global, it is also one in which the Middle East’s role is key – after all, this region has huge potential for renewable energy, even as some of its constituent nations are heavily dependent on fossil fuels. The broader MENA region is one in which climate-related risks are high, with the World Bank warning that climate change will reduce the amount of land available for agriculture, make cities even hotter, and put greater pressure on scarce water resources.[33]

Those challenges aren’t unique to the MENA region, of course, which is why central banks and regulators around the world have started working on ways to help the banking sector better incorporate climate-related risks into their business models and risk assessments.

Some regulators have made progress on standards and taxonomies to measure progress at a bank and industry level. More will follow their lead – and they need to, not least because this aspect lacks international standards.

Yet while drafting standards, taxonomies, guidelines and regulations is important, it’s equally important that central banks and regulators have the means to measure how banks and other FS participants are faring. Achieving that will require much better use of data to measure, gather and process progress.

Central banks and regulators also face tough decisions in how best to oversee the space in which climate risk and finance overlap. Success means finding a balance between regulation and encouragement – for example, whether to ease capital requirements for loans that promote climate initiatives or to mandate that a certain portion of banks’ loan books is allocated to that area.

Additionally, actions speak louder than words. Central banks can issue green bonds whose proceeds fund climate-positive initiatives, and they can ensure that their own assets are invested responsibly.

The reality, of course, is that some solutions will prove controversial. Yet failing to act will prove far more problematic. The risks of climate change require that central banks and regulators get involved. At this stage, the discussion needs to be not whether they should act, but how best they can do so.