The Hawaiian economy has so far withstood a harsh reversal of fortune tied to the coronavirus pandemic.

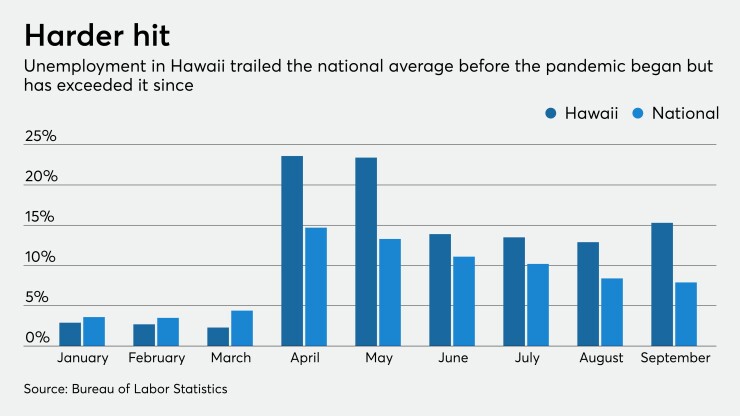

The state’s economy had thrived for more than a decade, drawing visitors from the U.S. mainland, Canada, Japan and elsewhere. Unemployment in the tourism-centric state hovered just above 2% in March and hotels regularly had high occupancy rates.

Then the pandemic hit.

By April, Hawaii’s tourism industry had essentially shut down, and despite fits and starts over the summer it is only now trying to fully reopen. The jobless rate was 15.3% in September after peaking at 23.6% in April — and University of Hawaii economists fear it could remain in the double digits into next year.

Hotel occupancy on Oahu Island, home to Honolulu, was 20% in mid-August, according to the American Hotel & Lodging Association. The rate was 89% a year earlier.

The state’s banks have yet to report major issues in their loan portfolios. While prior prosperity has allowed borrowers and lenders time to build buffers to withstand the pandemic’s initial shock, bankers are warning that 2021 could be the tipping point when it comes to credit quality.

Customers “really point to 2021 as a restarting year for us” before returning to “a meaningful level of activity” in 2022, Peter Ho, chairman and CEO of the $20 billion-asset Bank of Hawaii, said during a recent call to discuss quarterly results.

The hospitality industry, which accounted for a fifth of Hawaii’s pre-pandemic workforce, remains the biggest area of concern. More than half of retail revenue in the state has been tied to tourism.

“We anticipate property loans in [the hospitality] space could experience additional stress,” Robert Harrison, chairman and CEO of the $23 billion-asset First Hawaiian Bank, said during his company’s earnings call.

Hawaii took steps to contain the virus, requiring visitors to quarantine to two weeks after arriving in the state, though the effort crippled the tourism industry. The state considered lifting the rule in August, but kept it in force because of surges on the island and the mainland.

Over the last two weeks of October, visitors arriving daily in Hawaii ranged from 5,000 to 8,000, up notably from 2,000 in previous months but far below the 30,000 daily arrivals before the pandemic, according to state data.

The state recently started a pre-testing program for transatlantic travel, allowing for some optimism for a recover in tourism, bankers are not ready to budge on their tempered expectations for coming quarters.

“Our overall outlook on the economy hasn’t changed significantly since the second quarter as we continue to actively manage our credit risk,” Harrison said. “It’s still the early days for the economy in Hawaii.”

Mufi Hannemann, president of the Hawaii Lodging and Tourism Association, called 2020 “horrific,” though he expressed hope that the state’s economy and labor market will “slowly be able to reverse the trends that we've experienced for the past several months.”

Bank of Hawaii and First Hawaiian entered the downturn with robust capital levels, pristine credit quality and long runs of strong profitability. Both posted solid profits in the second and third quarters, and industry observers are confident that each can make it through a protracted coronavirus crisis.

At Bank of Hawaii, nonperforming assets made up just 0.16% of total loans on Sept. 30, a slight improvement from the end of 2019. Deferred loans fell to 9% on Oct. 23 from 16% on June 30.

While those metrics are viewed positively,

First Hawaiian said about 6% of its borrowers continued to defer loans, and nonperformers remain low.

“We're going to expect to see some deterioration in asset quality metrics in the portfolio,” Ralph Mesick, First Hawaiian’s chief risk officer, said during the company’s earnings call. “But if the provision can stay relatively benign … maybe we could change our outlook.”

“We agree with management’s outlook that we are in the early stages of the cycle and are closely monitoring arrival data to gauge the rebound in tourism,” Piper Sandler analyst Andrew Liesch said in a report.

The $6.6 billion-asset Central Pacific Financial in Honolulu, which has also remained profitable, said about 6.5% of its loans were on deferral at Sept. 30, or roughly half the level it reported a quarter earlier.

But Central Pacific warned that more challenges lie ahead. Loan downgrades — an indication of potential stress — rose in the third quarter, and the company said any recovery depends on tourism numbers.

“We're going to have to see, with the opening of tourism, what the implications will be to the economy,” Chairman and CEO Paul Yonamine said during Central Pacific’s earnings call.

The housing market, another key to Hawaii’s economic success, is holding up well. Ultralow interest rates are fueling

While First Hawaiian braced for issues with consumer borrowers, “the return to pay has been fabulous,” Mesick said, though concern remains that asset quality could deteriorate as government stimulus wears off and borrowers struggle anew to cover their expenses.

The state’s rental market is flashing

Before the epidemic, 95% of tenants would have paid their rent by midmonth and fewer than 3% would have 30- or 60-day delinquencies. On Aug. 15, the share of tenants current on their rent fell to 85%, while severe delinquencies topped 8%.

“This trend is troubling,” Garboden said. Unemployment figures “suggest that a substantial portion of those households have experienced at least one job loss, forcing them to sacrifice well-being to pay their rent.”

Barring meaningful economic improvement — or more federal aid — missed rent payments could mount. Property managers told Garboden’s group they estimate that 60% of tenants have endured financial setbacks.

“Landlords and property managers can’t know everything about what their tenants are going through, but their assessment of their tenants’ financial situation is sobering,” Garboden said.